Longevity is a tricky topic in software development.

We’ve been thinking about how we can make sure that Harmony continues to operate for a long time in the future, since Harmony is intended as a public good for researchers to use with no strings attached (an open source tool for social science).

In April 2023, we completed the software sustainability assessment with the Software Sustainability Institute, which gave us 29 recommended improvements to make Harmony more sustainable. By September 2023, we had introduced a number of improvements to the project and now have 14 recommendations remaining.

Read the April 2023 sustainability report.

Read the September 2023 sustainability report.

Read our blog post on the SSI’s website here

For the first iteration of Harmony, we developed the dashboard in Plotly Dash, and deployed it to an .org domain running on Microsoft Azure App Service. The website was running in Wordpress, hosted on Siteground. All of these are paid solutions which were coming out of the project budget.

We found that Wordpress is not a good long-term solution, since it needs to be maintained and updated to reduce the risk of security breaches. It would also not be compatible with any solution where we would host on infrastructure run by Ulster University, due to security concerns. Furthermore, Wordpress needs paid hosting for a good user experience, although free offerings are available.

We have taken the decision to migrate our blog from Wordpress to Hugo, and we have registered the domain harmonydata.ac.uk via Ulster University. This ensures a more authoritative domain, making us more findable and giving us a more permanent presence in UK academia. The Hugo website/blog is static, and managed from a Github repository and hosted on Github Pages. This is free and easy to work with - any member of the team can upload a blog post in Markdown format into the Github repository and the site is automatically rebuilt.

With regards the Harmony API, initially we ran the tool on Microsoft Azure. This was costing about £100-£200 per month, since the tool needs to run an LLM (large language model) in the background.

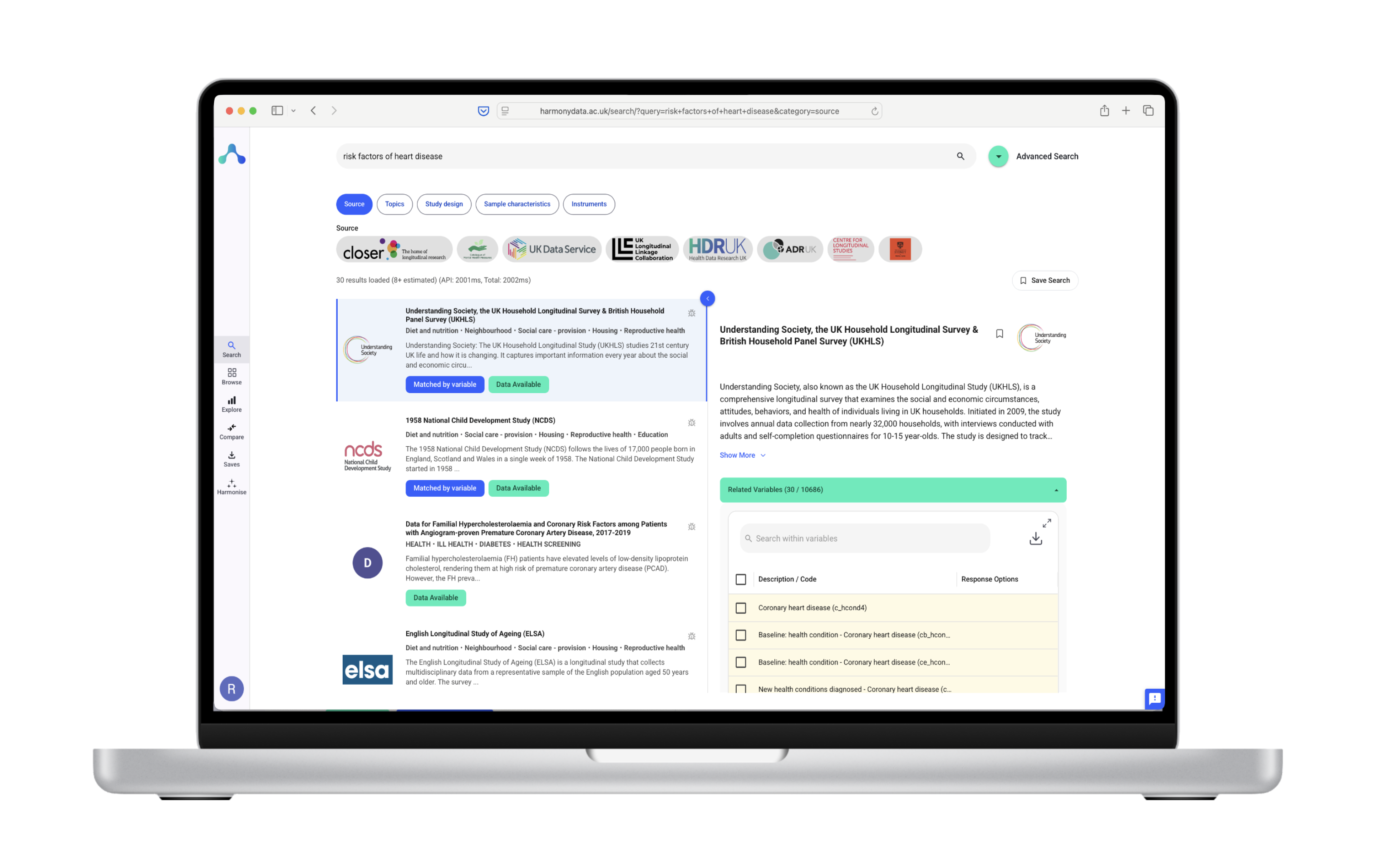

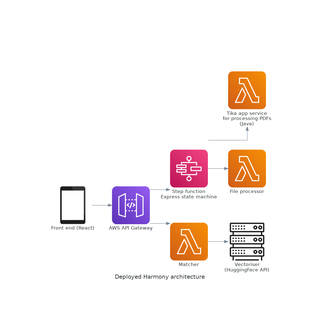

We explored a number of solutions which can cut costs, and we have chosen to use the available servers in Ulster University for ongoing hosting, meaning that an Azure account is no longer needed. An alternative which we explored was serverless (function as a service, or FaaS) solutions using AWS Lambda, which is cheap to run, but is very complicated to set up and results in long cold start times.

Alternative serverless deployment on AWS Lambda

We have developed our software in accordance with best practices of open source projects. Our Github repository is publicly available and we have also posted our code on the Open Science Foundation (OSF) here: https://osf.io/bct6k/.

We undertook a sustainability evaluation with the Software Sustainability Institute at the start of the Prototyping Phase of the Wellcome Data Prize. This highlighted some weaknesses of our software sustainability strategy, such as lack of clear information on licensing, how to contribute, or install the code. To correct these issues we have thoroughly updated the blog with the necessary information, and ensured that our software license (MIT) is prominent in all repositories and source code.

We’ve also ensured to release our tool in both Python and R, two of the most commonly used programming languages by researchers. Our API documentation is available online as a PDF download, and we’ve provide a series of videos on our YouTube channel to help you get started with installing and using Harmony.

For completeness, we have included our initial sustainability evaluation report from software.ac.uk (the Software Sustainability Institute) below.

This software evaluation report is for your software: Harmony. It is a list of recommendations that are based on the survey questions to which you answered “no”.

If no text appears below this paragraph, it means you must already be following all of the recommendations made in our evaluation. That’s fantastic! We’d love to hear from you, because your project would make a perfect case study. Please get in touch (info@software.ac.uk)!

Question 1.1: Does your website and documentation provide a clear, high-level overview of your software?

The fundamental questions that will be asked about your software are what does it do, what makes it better than other software that serves a similar role, and how does it contribute to research? Potential users should be able to easily find a one- or two-sentence description of your software on your website and within your documentation.

It can be difficult to quickly, and concisely, summarise your software, especially when you’ve spent months coding hundreds of exciting and powerful features. However, unless you catch the attention of a potential user very quickly, you risk losing them as a real user!

Question 1.3: Do you publish case studies to show how your software has been used by yourself and others?

A great way of showing off your software is to write case studies about how yourself, and others, have used it. Case studies can help potential users learn about your software. They also act as a great advert for your software. If you can show happy users benefiting from your software, you are likely to gain more users.

Question 3.1: Is your software available as a package that can be deployed without building it? Building software can be complicated and time-consuming. Providing your software as a package that can be deployed without building it can save users the time and effort of doing this themselves. This can be especially valuable if your users are not software developers. You should test that your software builds and runs on all the platforms it is meant to support, which means you will already have created packages that can be distributed to your users! See our guide on Ready for release? A checklist for developers.

If you’re interested in the consequences of ignoring your users’ needs, see our guide on How to frustrate your users, annoy other developers and please lawyers.

Question 4.6: If your software can be used as a library, package or service by other software, do you provide comprehensive API documentation?

If your software includes support for Application Programming Interfaces (API), whether these be functions, data types, or classes offered by a library or a collection of REST (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Representational_state_transfer) endpoints or web services, then these need to be documented if you want them to be used. Code examples alone may not provide enough information on how someone can use your API in their own code.

From structured comments in the code, generating complete, structured API documentation can be done automatically with, for example, JavaDoc (http://www.oracle.com/technetwork/java/javase/documentation/index-jsp-135444.html) (for Java), Doxygen (http://www.stack.nl/~dimitri/doxygen/) (for C, C++ , Fortran or Python), Sphinx (http://sphinx-doc.org/) (for Python). Certain REST frameworks, such as Django also support auto-generation of API documentation.

Question 4.8: Do you publish your release history e.g. release data, version numbers, key features of each release etc. on your web site or in your documentation? A release history allows users to see how your software has evolved. It can provide them with a way to see how active you are in developing and maintaining your software, in terms of new features provided and bugs fixed. Software that is seen to be regularly fixed, updated and extended can be more appealing than software that seems to have stagnated.

Question 5.1: Does your software describe how a user can get help with using your software? When a user discovers a problem, they’ll be sitting at their computer using your software. This means that the first place they will look to try and find a solution is in any help available with your software. If you have a graphical user interface, you should always have a “help” menu or an equivalent. For command-line tools a “–help” flag or a README file can provide this information. For online services, a link to a support web page is useful.

Likewise, if a user is looking at your documentation, there’s a good chance they’re looking to solve a problem, so it makes sense to also describe how a user can get more help there, too. It is important to describe how a user can submit their support request, for example, via e-mail, telephone, issue tracker, forum or other means, and any related resources e.g. web pages with frequently-asked questions or e-mail archives. It is also important that any of these resources remain available for the anticipated lifetime of the software, at least!

See our guide on Supporting open source software. Its advice applies to supporting closed source software too.

Question 5.2: Does your website and documentation describe what support, if any, you provide to users and developers?

The level of support that a user can expect to receive is often a vital element in a user’s choice of software. This means that the support you provide – whether it’s a guaranteed response in twenty-four hours, or a possible response on a best effort basis – needs to be made clear on your website and in your documentation.

This information can help manage users’ expectations. A user will always want their problem to be solved as quickly as possible, and may become disgruntled (and might even stop being a user) if this is not the case. If you are clear and honest about the level of support you can provide, then you are more likely to keep your users happy.

See our guide on Supporting open source software. Its advice applies to supporting closed source software too.

Question 5.3: Does your project have an e-mail address or forum that is solely for supporting users?

E-mail is purpose-made for resolving users’ problems. The user can provide a good description of their problem and can attach screenshots, log files or other supporting evidence, and it’s easy for you to ask for follow-up information, if required. You should always try to have an e-mail address for support queries.

It’s best if the support e-mail address is clearly labelled as such e.g.

myproject-support@myplace.ac.uk. This makes it easy for users to identify the e-mail address on your website or within your documentation, and it helps you to separate your support queries from all of your other e-mail. However, a personal e-mail address is better than nothing if you don’t have the means to provide a dedicated support address.

See our guide on Supporting open source software. Its advice applies to supporting closed source software too.

Question 5.4: Are e-mails to your support e-mail address received by more than one person? It’s easy to forget about an e-mail, especially one that’s asking difficult questions, so your e-mails to your support e-mails address should always be received by more than one person. One person should still have the primary responsibility of handling users’ e-mails, but others can step up to handle e-mails if necessary, so that a user’s query will be acknowledged even if one of you is on holiday, ill or otherwise indisposed.

See our guide on Supporting open source software. Its advice applies to supporting closed source software too.

Question 5.5: Does your project have a ticketing system to manage bug reports and feature requests?

Dealing with one or two support queries is straightforward enough, but as the number of queries grows and their complexity increases, it gets easier to make mistakes. Nothing will annoy a user more than their support queries being ignored, even by accident.

A ticketing system allows you to organise support queries in a scalable way. It provides an easy method to record who asked what, and when, to store additional information about the query, to assign someone in a team to handle a specific query, and to prioritise queries so that you can work on the most important first. A ticketing system is an absolute requirement if you have more than one person working on the queries – it prevents two people accidently working to solve the same problem, and allows you to easily keep up to date with progress.

Ticketing systems are also very handy at providing statistics. You can find out the components of your software that cause the most problems, then improve them or better document their use. You can also see how quickly you are dealing with issues, and check that you are meeting the level of support that you have advertised.

Examples of ticketing systems include JIRA, Bugzilla and Trac. Many third-party repositories, including GitHub, BitBucket, LaunchPad and SourceForge also provide issue trackers. See our guide on Supporting open source software. Its advice applies to supporting closed source software too.

Question 5.6: Is your project’s ticketing system publicly visible to your users, so they can view bug reports and feature requests?

An open ticketing system allows your users to see that you are active in fixing bugs and implementing features, and are responsive to your users. This can give them confidence in you and your software and makes them more likely to use it. It also provides your users with a means to see if a problem they have is a known issue, and allow them to check progress on it, or, even, whether their issue has already been addressed and a fix is available.

See our guide on Supporting open source software. Its advice applies to supporting closed source software too.

Question 6.1: Is your software’s architecture and design modular?

Modularity is a fundamental software design approach centred on the creation of self-contained functional units, or modules which serve specific purposes (e.g. file I/O, authorisation, logging, linear algebra, computational fluid dynamics, DNA matching, or text analysis).

Modularity has many benefits. It’s easier to reuse modules in other software, rather than re-implementing their functionality, saving both time and effort. Each module is self-contained, so it can be changed or updated without affecting the other modules in the code, and it can also be tested is isolation, which is useful when developing as part of a team. Modular designs are also easier to understand.

Given that source code is the final realisation of a design, it too should be modular and structured in a way that makes the modules clear. Programming languages support many ways in which a modular design can be realised e.g. packages and classes in Java; packages, modules and classes in Python; header files, source code files and data types in C; namespaces and classes in C++; or modules and classes in Fortran.

See our guide on Developing maintainable software and Modular Design on Wikipedia.

Question 11.5: Does your documentation list the version number for all third-party dependencies?

Different versions of languages, libraries, packages, scripts, models or tools can support different features. Code written to use one version of a language, library or package may not be compatible with earlier or later versions. You must provide information on what versions of dependencies users need to use when building, deploying or running your software. A user will be irritated if trying to use your software with Python 3 only to discover it is only compliant with Python 2, something which you, as its developer may have already known. You know what versions you use, so document these to help your users too.

Alternatives to version numbers include, depending upon where the dependency originates: a

source code repository commit identifier or tag, or a download date.

See our guide on How to cite and describe software.

Question 11.6: Does your software list the web address, and licences for all third-party dependencies and say whether the dependencies are mandatory or optional? Users don’t want to have to search the web for your third-party dependencies to find the information they need to package or deploy your software. You already know all the information that your users will need about suitable versions, licences and suchlike, so you should make it available to your users. In particular, licence information is very important, because users need to understand the terms and conditions of third-party dependencies so that they can determine whether they are legally permitted to use them, and, so, use your software.

Question 11.7: Can you download dependencies using a dependency management tool or package manager? e.g.Ivy, Maven, Python pip or [setuptools (https://pypi.python.org/pypi/setuptools), PHP Composer, Ruby gems, or R PackRat Bundling all third-party dependencies with your software means that your users don’t need to download the dependencies. However, it can lead to a very big release packages and, in some cases, you will not be able to bundle a dependency, because its licence prevents it. Dependency management tools provide automated frameworks to download and install third-party dependencies at build or deployment time. This helps to reduce the size of release packages, avoid licensing issues and save users from having to download dependencies themselves.

Question 12.1: Do you have an automated test suite for your software?

After changing your code and rebuilding it, a developer will want to check that their changes or fixes have not broken anything. Tests contribute to a fail-fast environment, which allows the rapid identification of failures introduced by changes to the code such as optimisations or bug fixes. The lack of tests can dissuade developers from fixing, extending or improving your software, as developers will be less sure of whether they are inadvertently introducing bugs as they do so. Each test might verify an individual function or method, a class or module, related modules or components or the software as a whole. Tests can ensure that the correct results are returned from a function, that an operation changes the state of a system as expected, or that the code behaves as expected when things go wrong.

There are many frameworks available for writing tests in a range of languages, including JUnit for Java, CUnit for C, CPPUnit and googletest for C++, FRUIT for Fortran, py.test (http://pytest.org/) and nosetests for Python, testthat for R and PHPUnit for PHP.

Automating the run of your test suite means the entire set of tests can be run in one go, making life easier for your developers. Having an automated build system is a very valuable precursor to providing a test suite, and having an automated build and test system is a valuable resource in any software project.

See our guides on Testing your software and Adopting automated testing.

Question 12.2: Do you have a framework to periodically (e.g. nightly) run your tests on the latest version of the source code?

Having an automated build and test system is a solid foundation for automatically running tests on the most recent version of your source code at regular intervals e.g. nightly. At its simplest, this can be done by scheduling a cron job on Unix/Linux or Mac OSX, or using Windows Task Scheduler. A

more advanced solution is to use a framework like Inca (http://inca.sdsc.edu/) which harnesses a number of machines through a central server to distribute a wide variety of tests in a parallel and scalable way.

See our guide on Testing your software.

Question 12.3: Do you use continuous integration, automatically running tests whenever changes are made to your source code?

Having an automated build and test system is a solid foundation for automatically running tests on the most recent version of your source code whenever changes are made to the code in the source code repository. This means your team (and others if you publish the test results more widely) obtain very rapid feedback on the impact of changes. Continuous integration servers can automatically run jobs to build software and run tests whenever changes are committed to a source code repository. For example, Jenkins (http://jenkins-ci.org) is a continuous integration server that can trigger jobs in response to changes in Git, Mercurial, Subversion and CVS. Travis CI (http://travis-ci.org) is a hosted continuous integration server that can trigger jobs in response to changes in Git repositories hosted on GitHub (https://github.com).

See our guides on How continuous integration can help you regularly test and release your software, Build and test examples (which includes walkthroughs on Getting started with Jenkins and Getting started with Travis CI), and Hosted continuous integration. Going further, this can also be done automatically whenever the source code repository changes. See our guides on Testing your software, Adopting automated testing (http://github.com/softwaresaved/automated_testing/blob/master/README.md)

Question 12.4: Are your test results publicly visible?

Publishing test results from frequently run tests (e.g. nightly build and test runs) can give your users reassurance about how, and how much, your software is tested. You can automatically publish test runs to your project website, or, alternatively, have test run results mailed to a developer’s mailing list, or a mailing list dedicated to the test results. For example, see the test results for the Taverna workflow management system which uses Jenkins to build and test their code, and publish its results.

Question 12.5: Are all manually-run tests documented?

[yes/no/non-applicable]

It may not be possible, or easy, to automate certain tests e.g. testing a browser-based application after it’s been deployed. In such cases, you should document the list of steps that are to be done to test the software. Documenting the steps means that the tests can be run by anyone, not just the

developer who usually does these tests.

Question 12.5: Are all manually-run tests documented?

It may not be possible, or easy, to automate certain tests e.g. testing a browser-based application after it’s been deployed. In such cases, you should document the list of steps that are to be done to test the software. Documenting the steps means that the tests can be run by anyone, not just the developer who usually does these tests.

Question 13.2: Does your website state how many projects and users are associated with your project?

Where you have an active set of users and developers, advertising their existence is not just good for promoting the success and life of your project. If potential users see that there are a large number of users, they know that your project is thriving, your software is useful and is under active development. This may encourage them to use your software, knowing that if they run into problems, there may be people who can help, and who they can share experiences with.

Question 13.3: Do you provide success stories on your website?

A great way of showing off your software is to write case studies about the people who’ve used it and how they’ve used it. This helps potential users learn about the software but, more to the point, is a great advert for your software. If you can show happy users benefiting from your software, you are likely to gain more users.

Question 13.8: If your software is developed as an open source project (and, not just a project developing open source software), do you have a governance model?

A governance model sets out how a, open source project is run. It describes the roles within the project and its community and the responsibilities associated with each role; how the project supports its community; what contributions can be made to the project, how they are made, any conditions the contributions must conform to, who retains copyright of the contributions and the process followed by the project in accepting the contribution; and, the decision-making process in within the project.

Though they are designed for open source projects, many of their concerns are relevant to any software project.

OSS Watch provide an introduction to governance models.

Question 14.2: Do you have a contributions policy?

A contributions policy provides information to users on what they can contribute (e.g. bug fixes, enhancements, documentation updates, tutorials), how they can contribute it (e.g. via e-mail, patch files, GitHub pull requests), any requirements they must satisfy (e.g. compliance to coding or style conventions, passing required tests, software licensing), and what happens to their contributions once they have submitted it (e.g. how it is reviewed and then integrated into your code, documentation or web site). It also tells users who owns the copyright on their contribution. For information on how to manage contributions, see OSS Watch’s Contributor Licence Agreements.

Question 14.3: Is your contributions’ policy publicly available?

Users may not contribute if they do not know that they can contribute. Publishing your contributions policy provides information to users on what they can contribute, how they can contribute it, any requirements they must satisfy, and what happens to their contributions once they have submitted it. It also tells users who owns the copyright on their contribution.

For information on how to manage contributions, see OSS Watch’s Contributor Licence Agreements.

Question 14.4: Do contributors keep the copyright/IP of their contributions? Asking contributors to sign over their copyright and intellectual property to your project or organisation can put off users from contributing. It, in effect, asks them to give away ownership of something that may be novel and which may represent a key aspect of their research. Allowing contributors to keep their own copyright and intellectual property removes this barrier, thereby making contribution a more attractive option. It also contributes to promoting a community round your software – everyone sharing their outputs rather than handing them over to a select group. For information on how to manage contributions, see OSS Watch’s Contributor Licence Agreements.

Question 15.2: Does each of your source code files include a copyright statement? It’s easy to distribute source code files, and this separates the code from any copyright statement that might be on your web site or in your documentation. To cover this eventuality, and remove any ambiguity about ownership, it’s good practice to include a copyright statement with each of your source code files, as a comment, or, if the language permits it, as a string constant.

Question 15.3: Does your website and documentation clearly state the licence of your software? Users need to know the licensing conditions of your software, and also any third-party software bundled with it, since this may impose constraints and obligations on how they can use or redistribute it. Developers need to know the conditions under which they can change or extend your software and any restrictions on their modifications and extensions and the redistribution of these. It is also essential for users and developers to know the licencing of any third-party software bundled in a release for the same reasons. This can include: third-party source code, copied in and used as-is; modified, extended, or bug-fixed, third-party source code; third-party binaries (e.g. DLLs, JAR files etc) shipped by you; and, third-party software that is downloaded and installed by users.

If users can view the licence for your software on your website, without having to download your software, then potential users can quickly determine if the licence is suitable for how they intend to use your software.

If you don’t have a licence, and an open source licence might be right for you, then see our guide on Choosing an open-source licence.

Question 15.6: Does each of your source code files include a licence header? It’s easy to distribute source code files, and this separates the code from any licence statement that might be on your web site or in your documentation. To cover this eventuality, and remove any ambiguity about what a developer can do with the source code, it’s good practice to include a licence statement within each of your source code files, as a comment. This can also help to avoid confusion between source files that may have different licences, particularly if there are a number of third-party dependencies used within your software.

Question 16.1: Does your website or documentation include a project roadmap (a list of project and development milestones for the next 3, 6 and 12 months)?

A roadmap allows users to see when new features will be added and plan their project accordingly. It also has an important secondary benefit: one of the most important factors that will influence a user’s choice of software is the likelihood of that software still being around – and supported – in the future. There are many ways in which a project can persuade a user of its longevity: regular announcements, regular releases, prompt replies to queries, information about funding and its plans for the future – a roadmap.

Question 16.2: Does your website or documentation describe how your project is funded, and the period over which funding is guaranteed?

Especially on academic projects, users will view the active lifetime of software to be the duration of the software’s project funding. If you want to persuade users that your software will be around in the future, it is a good idea to describe your funding model and the duration over which funding is assured.

Question 16.3: Do you make timely announcements of the deprecation of components, APIs, etc.?

It’s never a good idea to remove components or features without giving your users an advance warning first. It could be there are users who are dependent on the feature(s) you plan to change or remove. Announcing such planned deprecations well in advance means users and developers can respond if a given feature is important to them.

If a feature is due to be superseded by a newer, better feature or component, including both for a suitable period within the software can allow your users to transition comfortably from the older version to the new version.

You could also consider developing and publicising a deprecation policy, stating how and when features or components in general are deprecated. This gives your users assurance that features will not be removed without warning. see, for example the Eclipse API deprecation policy.