Many psychologists believe that mental illnesses can vary across cultures. In 1904, Emil Kraepelin initiated the field of comparative psychiatry after studying mental health disorders in Java, writing that “Die Eigenart eines Volkes wird auch in der Häufigkeit und klinischen Gestaltung seiner Geistesstörungen zum Ausdruck kommen,” meaning “The peculiarity of a people[ethnic group] will also be expressed in the frequency and clinical form of its mental disorders.”[1]

More than a century later, the emergence of global mental health research projects has opened a number of debates about the applicability of psychiatric categories to different cultural settings, such as those in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) series[2].

In 2013, the publication of DSM-5 included for the first time Cultural Concepts of Distress (CCD), referring to “ways that cultural groups experience, understand, and communicate suffering, behavioral problems, or troubling thoughts and emotions”[2].

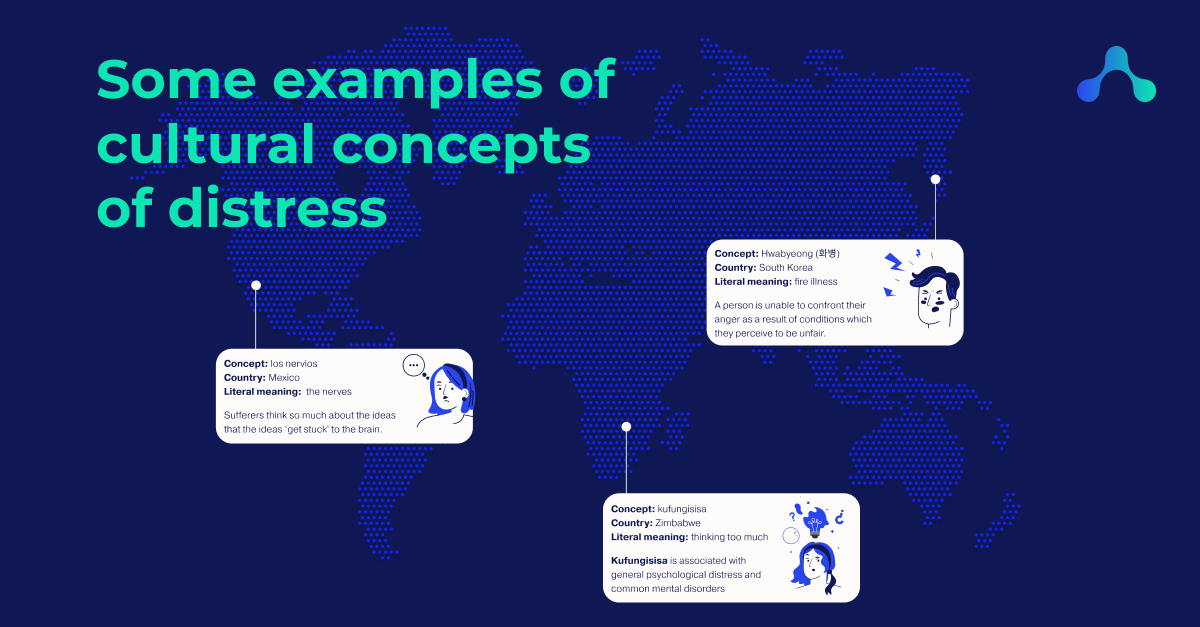

Examples of cultural concepts of distress include:

Can we use Harmony to harmonise mental health instruments designed for different cultural settings where some disorders may have no direct equivalent in one culture?

Zvaita sei kuti chembere yorasika, bere rorutsa imvi? (How is it that the old woman is missing and the hyena is vomiting grey hairs?)

Shona proverb (similar to English “there’s no smoke without fire”)

If you are a Python user, you can follow my experiment in this Jupyter Notebook, which you can open in Google Colab: https://github.com/harmonydata/

Shona (chiShona) is spoken in Zimbabwe and belongs to the Bantu language family, which also includes Zulu, Xhosa, and Swahili.

| Shona | English |

|---|---|

| funga | think |

| kufunga | to think |

| ndofunga | I think |

| -isa | (causative suffix: “to cause to do”) |

| -isisa | (intensive suffix: “to do quickly”) |

| kufungisisa | think deeply, think too much; a Shona idiom for non-psychotic mental illness |

In Shona, derived verbs can be created from simple verbs by attaching suffixes to the verb stem.

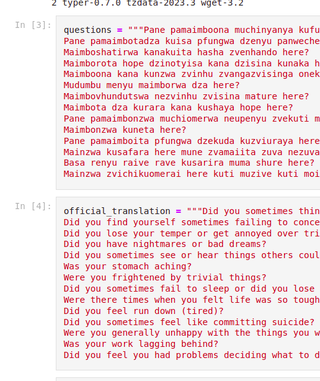

I tried using Harmony to see how it would harmonise “kufungisisa” (thinking too much) to a Western instrument such as GHQ-12.

Although English is the best-resource language for natural language processing, multilingual NLP techniques are catching up even for lower-resourced languages. There exist some NLP models for Shona. I used the sentence transformer model Davlan/xlm-roberta-base-finetuned-shona which is a modification of ROBERTA trained on Shona texts[7]. I plugged one into Harmony and tried to match the Shona symptom questionnaire for the detection of depression and anxiety, which is used in Zimbabwe[6].

Above: the text of the Shona symptom questionnaire for the detection of depression and anxiety.

A problem I encountered was that the transformer model didn’t work for both Shona and English (it’s not multilingual, like Harmony’s default transformer model). I Google translated GHQ-12 into Shona as a temporary measure.

Also, the transformer model did not operate as a sentence transformer, but rather as a token-level transformer, so my sentence vectors were made by averaging token vectors across an input.

My model’s output is below:

Harmony and the Shona transformer model matched the question about “kufungisisa” to GHQ-12 question 1 “been able to concentrate on whatever you’re doing?” which seems approximately OK. However, I would need a Shona native speaker to validate my results.

Also, when we are using English and Portuguese texts, which has until now been our go-to bilingual combination, we have had the advantage that some multilingual models cover both languages and so it’s possible to directly compare in both source languages. In the absence of an LLM (large language model) which can handle both Shona and English, it’s not possible to directly compare English and Shona text, but my experiment above shows that Harmony can work on monolingual Shona text.

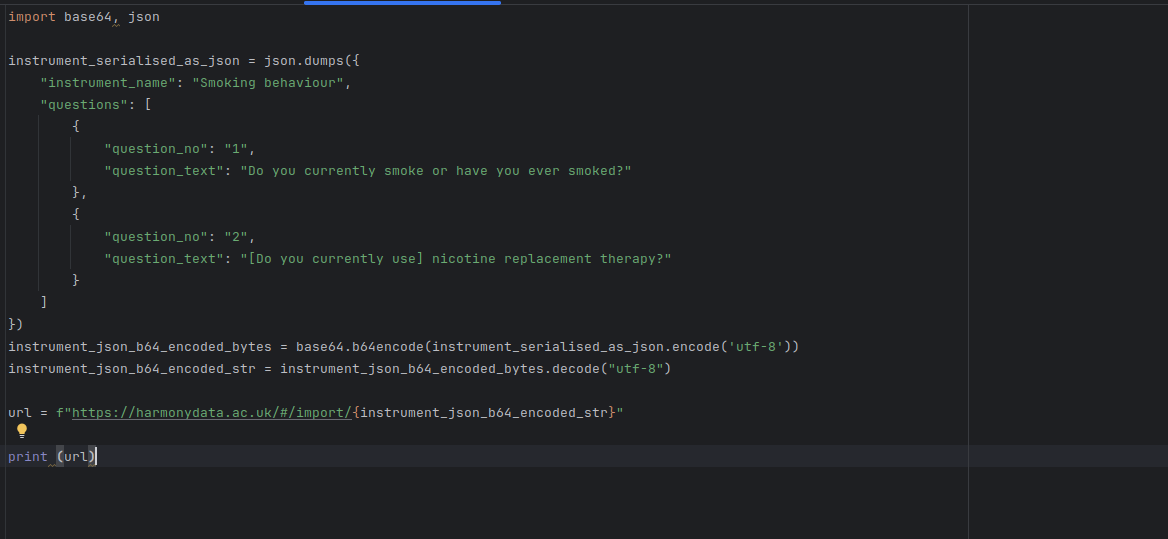

Sending data from another website to Harmony using Javascript We have exposed functionality for external websites to integrate with Harmony and add an “import to Harmony” button, either generated in Javascript or in Python. Create an Instrument object with at least an instrument_name and questions property in JSON - the questions must have a question_no and question_text properties eg: { "instrument_name": "Smoking behaviour", "questions": [ { "question_no": "1", "question_text": "Do you currently smoke or have you ever smoked?

Harmony at PyData London - 86th Meetup Update: you can download the slides from the presentation here Topic: NLP and generative models for psychology research Thomas Wood will present our work on Harmony, harmonydata.ac.uk, which is a free online tool that uses generative AI and LLMs to help psychologists analyse datasets. It uses Python, Pandas and HuggingFace Sentence Transformers to find similarities between questionnaires. Psychologists and social scientists often have to match items in different questionnaires, such as “I often feel anxious” and “Feeling nervous, anxious or afraid”.