Public administrations today are tasked with managing massive volumes of data in multiple formats, often using different management methods, as per the demands of their individual organisations. It’s also become common for them to host multiple copies of that data across different repositories.

As a result, the data can often be disseminated across multiple regions, especially in terms of content and presentation, unless it is ‘harmonised’. This is one reason why there is so much re-use at the low level of existing information on citizens and businesses, for example.

Data harmonisation in the public sector allows for the management of consistent and coherent data – and in a way that’s also compatible and comparable, ultimately, unifying definitions, formats, and structures across all locations.

While this shaping or harmonisation of data can be done separately for each project, it oversees a very high cost in terms of both time and resources. It’s, therefore, very important and even necessary to promote standards which allow public sector organisations to work with data that’s already harmonised.

In this in-depth article, we’ll be discussing some common applications of data harmonisation for the public sector.

The NIH (National Institutes of Health’) / NCATS (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences), NLM (National Library of Medicine), ONC (Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology), NCI (National Cancer Institute), and FDA (Federal and Drug Administration) – made a collaborative effort to build the necessary data infrastructure for conducting PCOR (patient-centred outcomes research) through the use of observational data acquired from healthcare delivery in routine clinical settings.

The main sources of this data were EHRs (electronic health records), patient registries, and insurance billing claims, to name a few. Naturally, for the purpose of achieving a sustainable data network infrastructure as well as promoting interoperability and fostering the creation of a proper LHS (Learning Health System), data must be mapped and transformed across multiple CDMs (Common Data Models), while also leveraging open-source standards.

The CDM organised data into a standard structure which initially differed across networks. With the collaborative project, multiple existing CDMs were harmonised to support research & analysis across several data networks. This aim facilitated the utility of data and its interoperability across all the various networks, in order to ultimately facilitate the PCOR.

The process of mapping various CDM data elements and leveraging existing PCORTF (patient-centred outcomes research trust fund) investments made it practical and feasible to reuse the existing data, methods and resources from each network – thus, providing PCOR researchers with a much larger and more diverse pool of observational data types.

The enhanced data infrastructure which resulted from this collaborative project can potentially support evidence generation on patient-centred outcomes to inform regulatory and clinical decision-making within the various federal-level programmes.

The project’s key achievements and highlights included:

Lots of data is generated on a daily basis along the entire food value chain, making heterogeneous data sources difficult to exchange and compare. This data harmonisation for public sector use case helped to produce more comparable and compatible datasets, where different tools and frameworks as well as methodologies were used for food data harmonisation.

Specific frameworks, tools, and data exchange formats were incorporated to generate comparable data sources. A number of studies have been conducted to date to overcome the issues of food data integration and interoperability. Food exposure assessments require combining data on food consumption with that pertaining to concentration of adverse chemicals in foods.

The food consumption data was formatted at different levels – e.g. food as consumed (bread or rice), ingredient (flour), and RAC level (Raw Agricultural Commodities like apples, tomatoes, wheat, etc.). Since the foods’ RAC components were comparable on a national scale, harmonisation for risk assessment procedures at the EU level and food consumption data would need to be formatted at the edible-RAC level only (in contrast, RAC without non-edible part would be a banana without the peel, e.g.). This was suggested by Boon et al. – describing an approach to format national consumption data at the RAC level and generate the respective RAC conversion databases, which can then be used for edible-RAC conversion.

The RAC conversion databases were then used at the EU level in environmental contaminants risk assessments – e.g. pesticides, heavy metals, glycoalkaloids and other chemicals.

Since there were multiple non-comparable formats which originated from different methods or software-based tools, data from heterogeneous sources to be combined with the food consumption data was originally proving to be cumbersome. Pakkala et al. proposed a data interchange format based on XML (Extensible Markup Language) which could be used as a common interface to link a variety of software tools.

Additionally, the FAO/WHO GIFT open-access platform, has been developed to harmonise individual quantitative food consumption data (IQFC), helping researchers evaluate the eating habits of different population groups according to their geographical location, particularly in low and middle-income nations. The platform today is a globally growing repository of IQFC microdata, where all the datasets are fully harmonised according to the EFSA’s (European Food Safety Authority) food classification & description system (FoodEX2) – allowing end users to easily aggregate the currently available data.

A more efficient and semi-automatic system was later introduced to classify and describe foods which follow the existing the FoodEX2 system, where machine learning (ML), natural language processing (NLP) and post-processing is used, boasting a general accuracy rate of 79%.

These food traceability systems contain the required information about foods at each stage of the food chain – from farm to fork. Information like this can be utilised for legal and quality standards compliance, and also for gaining better consumer trust.

Additionally, based on the above XML technology, Folinas et al. proposed a simple framework to help with traceability – a framework that’s not only easy to use, particularly at the bottom end of the supply chain (e.g. farmers, cattle breeders, fishermen, etc.) but also facilitates the exchange of information through commonly accessible items (email, phone, internet, etc.).

Pizzuti and Mirabelli also proposed a general framework based on a web-powered traceability system which can be queried for food related information at each stage of the food supply chain.

However, given the diversity of data models currently being utilised by food data providers, integration of information into a centralised database is not achievable – despite the fact that there are legal obligations in place for providing ingredient information on food packaging in certain countries, there aren’t any legal requirements for digitally providing information on the nutrient values, ingredients or allergens in a standardised format to consumers.

Munzberg et al. looked into the ETL process to help integrate data from heterogeneous sources into a centralised database. As part of a case study, the authors showed that data can be integrated from five unique sources into a single, centralised database. From that database, the information is transmitted to a health mobile app (used for health monitoring purposes) using a JSON format (JavaScript Object Notation) – an open-standard file format for data interchange which can be used to store and transmit data.

Achievements from the above include:

The Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health is currently testing a number of data-cleaning and harmonisation processes on example datasets, in addition to developing a publication which encompasses data harmonisation application findings and recommendations.

The Data Harmonisation Use Case (DHUC) project’s aim was to address the feasibility of using harmonised language for combining data across multiple EHS (environmental health science) research studies. They achieved this by applying data & metadata standards to example datasets – where the end goal was to develop a set of strategies as well as resources to facilitate and also encourage data sharing and harmonisation – in both present and future research efforts.

The impact of DHUC was as follows:

ASEDIE (Multisectoral Information Association) in 2019 launched an initiative for opening the ‘three sets’ of harmonised data in all the Autonomous Communities: the databases of cooperatives, associations, and foundations.

It was proposed that all communities should follow a unified criteria in order to facilitate reuse – for example, the incorporation of the NIF in each one of the respective entities.

The results were remarkable, so say the least. As of today, 15 Autonomous Communities have opened at least two of these three databases, while the Database of Associations has been opened by all of the 17 Autonomous Communities.

In 2020, ASEDIE revised the “Top 3”, promoting the opening of new databases titled: commercial establishments, industrial estates, and SAT registers.

However, not all Autonomous Regions have a register of commercial establishments as yet (it is not a regional competence, after all), which effectively replaced this dataset with the Register of Energy Efficiency Certificates.

Abbreviated as ‘FEMP’ in its Spanish singles, the Spanish Federation of Municipalities and Provinces has launched an open data group which has developed two guides to aid municipalities in implementing open data initiatives.

One of them pertains to a proposal of 40 datasets, stating that every administration must open to facilitate the reuse of public sector information.

Additionally, the guide aims to establish uniformity in the categories of the data published to date and also uniformity in terms of the way they are published. A fact sheet was created for every proposed dataset with information on the update frequency and the formats or suggested display form.

For the foreseeable future, FEMP has plans to include all the published reviews on datasets to assess whether it should add or remove certain datasets, and also to include new practical applications.

The challenges around integrating and utilisation of multicenter datasets has made researchers realise how important data harmonisation for the public sector is, when it comes to carrying out large-scale studies.

While the information fusion with harmonisation cannot quite achieve reproducible results in longitudinal and large scale studies, data harmonisation is still critical for patients that are being longitudinally monitored and imaged via different scanners.

For example, the longitudinal PET cannot offer any helpful information as it’s gathered from multi-scanners, leading to concealed or convoluted outcomes.

By deploying a computational method – which includes acquiring datasets like staining and scanning, pre-processing, modelling, and analyses – data harmonisation can be conducted in the background through the processing of images, signals, or gene matrices. Sample-wise harmonisation is typically conducted prior to modelling, where the aim is to reduce the cohort variance of the training samples, fusing multicentre samples as one dataset.

Similarly, feature-wise harmonisation will reduce the bias of extracted features – GLCM and convex hull area of a region of interest, for example. It’s typically performed on extracted feature matrixes, thus, eliminating the cohort variances by fusing the extracted features.

Both sample-wise and feature-wise data harmonisation in healthcare can reduce the underlying variances and, therefore, noticeably improve the performance and effectiveness of analysis.

For decades, computational data harmonisation has been proposed for digital healthcare research studies. However, until and unless data harmonisation is performed effectively, bridging the basic science research models and data fusion models into a multicentre, multimodal, and multiscanner medical practice as well as clinical trials – can be very challenging.

This research paper recommends the CHECDHA criteria to help researchers conduct data harmonisation studies in a standardised format, thus, advancing academic reproducibility and development.

While the above use cases may or may not accurately provide insights into how data harmonisation in the public sector can be highly advantageous, we believe these industry-specific applications should give you a fairly good idea about its practical usefulness:

Healthcare businesses, be they private or public can benefit by harmonising their data in several ways:

Banks, financial institutions and fintechs also stand to benefit monumentally from data harmonisation in the public sector:

Manufacturing players can better streamline their operations across the entire supply chain by:

The multi-billion dollar pharma and R&D industry can enjoy a number of benefits by adopting data harmonisation for public sector:

We’d like to close off the piece by sharing a great data harmonisation (public sector) example – Amgen, a multinational biotech company working with thousands of suppliers, who in turn, supply hundreds to thousands of medical and pharma items.

Amgen wanted to enhance their logistics intelligence in order to improve supply chain efficiency and also to better understand which items across which of their suppliers were the same – and also to do this far more efficiently.

Using a multi-model data platform along another one with semantic AI capabilities, they were able to harmonise data from disparate sources, creating a unified dataset which resulted in improved efficiencies.

You will likely come across many similar ‘day-to-day’ examples like these as adoption of data harmonisation in the public sector continues to increase.

In closing, data harmonisation for the public sector is something which can drastically boost organisational efficiencies by streamlining data processing and management. It helps to reduce the risk of errors by a broad margin and also the length of time needed to derive insights to make informed business decisions.

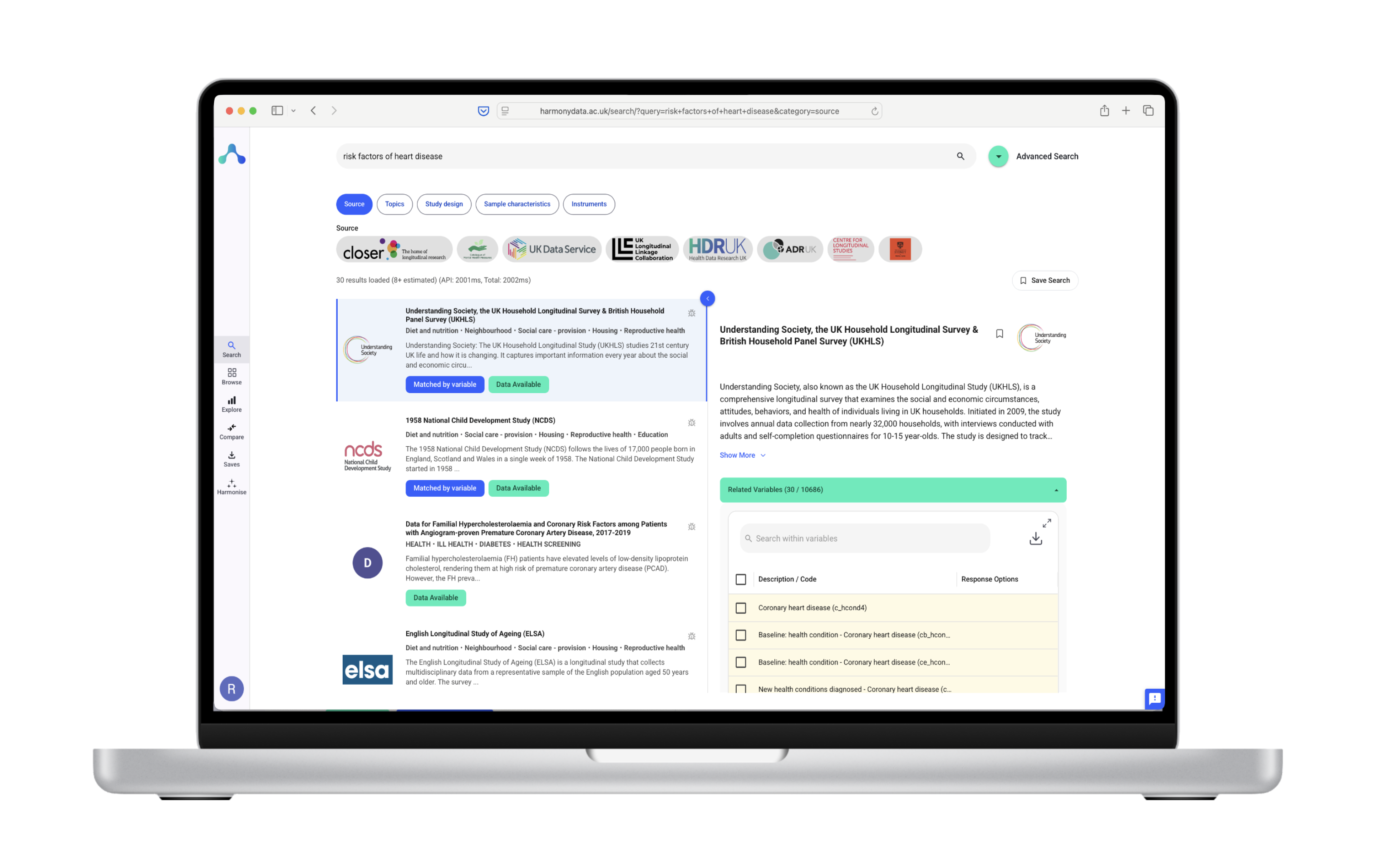

The Harmony app can help you overcome all kinds of data harmonisation (public sector) challenges, helping you embrace best practices to achieve your end goal in a far more efficient and cost-effective way.